4,50 €

In stock

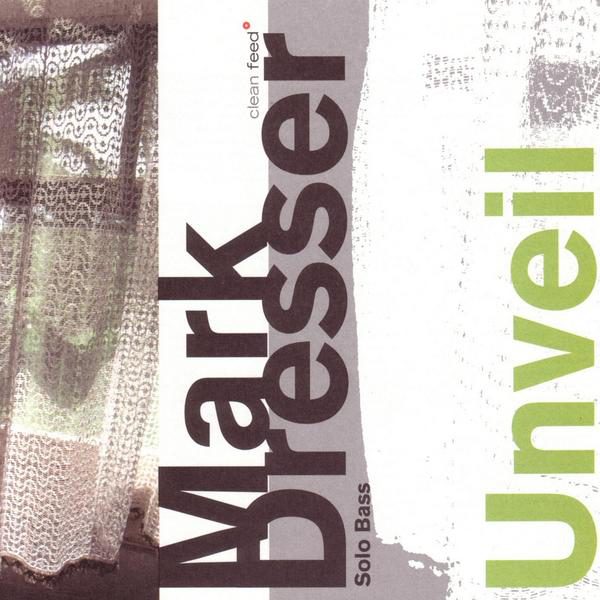

In a lesser known essay sub-titled “the Fantastic Considered as a Language,” Jean-Paul Sartre contends that fantasy literature manifests “our human power to transcend the human.” A writer achieves this through the “creation of a world in which … everything is both means and ends.” Much the same can be said of instrumentalists who create new modes of virtuosity that blur the line between material and method. The fantastic, Sartre concludes, “pursues the continuous progress which should ultimately reunite it with what it has always been.” Again, this roughly parallels the improviser who considers his instrument outside specific contexts of history and practice, approaching it simply as a sound-producing object or, as Steve Lacy referred to the soprano saxophone, an interval machine. The resulting new languages are at the heart of what is fantastic about contemporary music. Mark Dresser has created a fantastic language for the double bass, one that rivals any created with machines in its ability to fascinate. Why call it fantastic, and not simply abstract? When it is not functioning within narrative or representational contexts (scores for “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” and “Un Chien Andalou”; compositions whose subjects span Bosnia and the Marx Brothers), Dresser uses his language to pull the listener into, for the lack of a mushless term, another world; whereas, the abstract remains at arms length. The fantastic is often rooted in that which is hidden in plain sight. That is the case with Dressers music. Literally, stopping a bass string demarcates two pitches; since only the pitch below is normally played, the pitch above the stop remains obscured. The fantastic qualities of Dressers music stem from his techniques for playing above and below the stop, and his use of technology to amplify the complete string. Playing the complete string creates marked contrasts in pitch and timbre, which, when combined with other stopped and open strings, result in startling textures. Since the early 1980s, Dresser has refined several approaches to playing the complete string that are now central to his music, including two-handed string tapping and methods of pressuring and/or releasing the string. Transforming normally soft timbres into major, even defining components of a performance is an ambitious proposition, even if the artist is availed a pristine environment like IRCAM. But, Dresser has had to contend with the colliding realities of performance, hardware and travel. Dresser has overhauled the other components of his system at least twice, and has tweaked it on numerous other occasions, the only constant component being a volume pedal, which Dresser uses to shape the envelope and decay of sounds. He initially employed condenser microphones, whose faithful high frequency response is indicated for music, like Dressers, that privileges harmonics. However, problematic aspects of condenser mic use in ensemble settings, where they invariably pick up other instruments, tethered this methods development to solo studio recordings such as <>. Dresser then adapted a concept from guitarist Tom North, suspending pickups from the scroll of the bass, dubbing it the Giffus. However, stock single coil pickups are notoriously susceptible to noise, a tendency Jimi Hendrix artfully exploited, but a potential liability for Dresser. Still, pickups and preamps yield more pitch information relative to finger noise than condenser mics and phantom power. Subsequently, Dresser turned to sculptor Don Jacobson to refine the Giffus, who employed pickups designed by the renowned Bill Bartolini, which yielded both a superior signal to noise ratio and an appreciably warmer sound. Yet, even Bartolinis superior pickups became unstable after years of travel, performances and recording sessions, causing Dresser in 2002 to enlist Kent McLagan (who, in addition to being a bass player, is a luthier and an electronics engineer) to design a new, and yet unnamed, system using handmade coiled pickups that are embedded into the fingerboard. By placing them in two different positions, the system facilitates as many as three different pitches simultaneously on one string. Placement of a pickup just below the nut maximizes high frequencies while placement of a pickup at the minor 6th yields a more balanced spectrum of harmonics compared to placement at the 5th. This newest system is heard on every track of <> with the exception of the acoustic “Bacachaonne,” a dedication to Israel “Cachao” Lopez that is loosely based on a movement of Bachs second violin partita. Dressers deft manipulation of the system is immediately evident on “Lureal,” which begins with pitches otherwise imperceptible in an acoustic setting. “Clavuus” and “Cabalaba” are more extensive explorations of usually inaudible information; on the former, shifting left hand pressure on the string while engaging the pickup, resulting in buzzing, Jews harp-like timbres, while the latter revisits the bitones that have been a focus of Dressers work since before the inception of the Giffus. Dressers use of the volume pedal, which is roughly analogous to a master trap drummers finesse with a bass drum, continues to figure prominently in his music. On “Pluto,” Dresser uses the pedal to shape not just the envelope of the ringing harmonics he creates with his two-handed technique, but the overall tone — vibe, if you will — of the piece. The pedal-enhanced harmonics are even more arresting on the title piece and “Kathrom” by virtue of unorthodox tunings. The only edited, multi-track piece on the album, “Unveil” is also noteworthy because it exemplifies the contribution of Raz Mesinais engineering. On its face, Mesinais recording technique is straightforward: mic both the instrument and the speaker to mix the ordinarily inaudible details supplied through the pickup and the rich natural sound of the bass. Mesinais approach accentuates the ultrasonic quality of Dressers music, particularly when Dresser plays harmonic chords at the end of the piece, while reasserting the acoustic properties of the instrument as the musics foundation. The double bass has always had the capacity to make music such as Dressers; but, it needed Dresser to prove it. In the process, Dresser affirms the human endeavor of unveiling the fantastic.

Bill Shoemaker March 2005