4,50 €

In stock

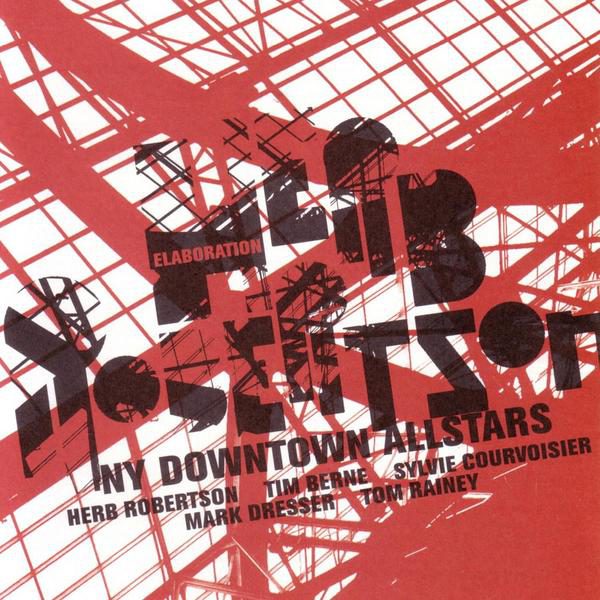

A new Herb Robertson release is always cause for celebration, at least in my household. There’s always that anticipation to see what he’s done this time. Ever since his first JMT releases in the mid-80s, (Transparency and X-Cerpts, both done with his early quartet of Tim Berne, Lindsay Horner and Joey Barron) Robertson has always delivered something different that discriminating listeners can sink their ears into. He released a superb album of Bud Powell compositions arranged for brass sextet and rhythm. His trio with bassist Dominic Duval and drummer Jay Rosen (a killer rhythm duo) put out a pair of records that specialized in free improvisation in its purest form yet could also essay a stunning rendition of that hoary old chestnut “Deep Purple”. Robertson has led large ensembles in free improv blowouts (Knudstock 2000) and he’s shared duo space with drummers (Phil Haynes on Ritual) and fellow trumpet players (Paul Smoker on drummer Jay Rosen’s Drums And Bugles). In addition to being a creative leader, Robertson has also been the consummate sideman. When Paul Smoker needed a fellow trumpeter for his brass trio recording Brass Reality, Robertson got the call. When, back in 1992, Joe Fonda and Michael Jefry Stevens were forming their long lasting group (Fonda/ Stevens Group), they needed a trumpet player who could play as outside as the music went, yet still be mindful of the tradition from which their music sprung. Robertson was the prime candidate. According to bassist Fonda, “Herbie was always the first choice.” Which brings us to Elaboration. For this date, he’s assembled a new ensemble, Herb Robertson’s Downtown All-Stars, a group handpicked from the illustrious list of players he’s performed with in the past. “In 2003, I was in Copenhagen and I ran into Ken Pickering, the organizer of the Vancouver Jazz Festival. He asked me when I was going to bring one of my bands to his festival. I’d appeared there before but only as a sideman. I thought this would be a chance to put a really interesting group together. I proposed the players and he went for it right away. I’d played with everyone before but in different contexts and I wanted to see how this group of players would work.” He knew exactly whom he wanted: alto saxophonist Tim Berne, pianist Sylvie Courvoisier, bassist Mark Dresser and drummer Tom Raney. “I was looking for players who are orchestrators on their instruments, players who are very confident and have their own sound. I had a piece in mind and my concept involved trying to get an orchestral architecture to it.” Robertson’s instincts served him well. Although everyone in the band had played with each other before, they’d never played together in one band. Four of the five players have a history going back over 20 years and they are players who know each other’s style well. “Tim and I met in 1981 at a jam session at a loft. It was a free improv session and I heard him play and it was like wow!” They got together and Robertson became an integral part of Berne’s early New York ensembles (and vice-versa). He’s played in several of Berne’s groups right up to the present day. “Last year in Europe, I was a guest with his Science Friction band.” He and Raney go back to around the same era. “I met Tom around 1985-86 in Brooklyn. Tim and I went to Bridge St. where Tom was living and we met him at a free session. Mark and I met around 1987. I met him through Joey Baron. Pianist Sylvie Courvoisier may seem to be the odd-person-out in this group but she’s had a history with Robertson since the mid-90s. “She’s from Lausanne, Switzerland. I met her through (violinist) Mark Feldman. I’d done some jam sessions with her and from that we did some duet improvisations in concert. Everyone else in the group has played with her as well. She’s an original player and an excellent orchestrator on her instrument.” Robertson wrote a new piece for a group: a suite revolving around written themes, full group interplay and subdivisions within the group. “It’s in twelve parts. One person told me they thought it was in thirteen parts and another said fourteen.” I heard three sections. “Yeah, David Torn said the same thing when he was mastering it. I look at all the duos, trios etc. as sections melding into each other. The written music was basically to set up improvising sections within the groups. I mapped it all out and tried to make it so it would keep moving.” There’s so much happening in this piece that it’s pointless to detail it. But highlighting a couple of spots might be in order. There’s a particularly effective moment where the first theme emerges. At four minutes, Tim Berne begins to play a figure repeatedly, recalling the type of thing John Tchicai used to do back in the late 60s when he would obsessively play a motive over again and again. “Tim’s great at introducing themes. And he’s great at sitting on things and tearing them apart and exploring them. I gave everybody the freedom to introduce themes whenever they felt like it.” Another high point occurs at 17 minutes, when an intense group section dies down and Sylvie Courvoisier begins an unaccompanied solo. Her solo sets up a chorale section which turns into a ballad featuring Robertson’s abstractly lyrical trumpet. The final portion of the piece finds Courvoisier delivering a full-throttle piano solo. “Yeah, that last part almost becomes a concerto for piano. I really wanted the piano to fill in the sound orchestrally.” Another highlight throughout is the aplomb demonstrated by the rhythm section of Dresser and Raney. They’re always in there, prodding and responding to the soloists, adding the right amount of rhythmic color and texture, fluidly segueing from section to section. As I said before, a new Herb Robertson is always an event. This one is no exception. So just put it on and listen. The music speaks for itself. It needs no further Elaboration.

Robert Iannapollo February, 2005